According to recent findings now published in Healio Rheumatology, patients with rheumatoid arthritis and periodontal disease may experience flares because bacteria from “leaky gums” move into their bloodstream and cause inflammation.

It has been shown that periodontal disease incidence is higher in individuals with RA, but is particularly prevalent in those with anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs), according to study authors Dana Orange, MD, associate professor of clinical investigation at Rockefeller University, assistant attending in rheumatology at the Hospital for Special Surgery, and William H. Robinson, MD, PhD, Stanford University professor of medicine.

Together with their colleagues, they suggest that this may implicate oral mucosal inflammation in RA pathogenesis.

Scientists conducted a paired analysis of human and bacterial transcriptomics in the current study, published in Science and Translational Medicine.

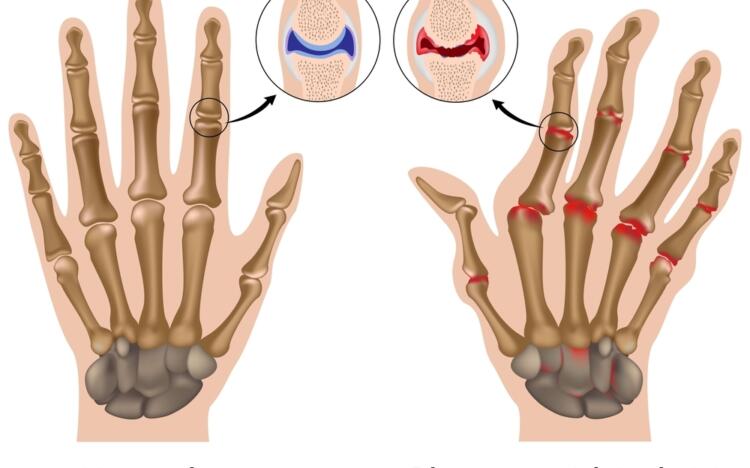

Researchers concluded that patients with both RA and periodontal disease experienced repeated oral bacteremias associated with transcriptional signatures of ISG15+HLADRhi and CD48highS100A2pos monocytes.

RA patients’ inflamed synovia also exhibits these signatures.

The oral bacteria in the blood, according to Orange, Robinson and colleagues, were “broadly citrullinated in the mouth, and extensively somatically hypermutated ACPAs encoded by RA blood plasmablasts targeted their in situ citrullinated epitopes.”

Periodontal disease can lead to “leaky gums” that allow citrullinated oral bacteria to enter the bloodstream and activate inflammatory monocytes in RA, according to the researchers. Furthermore, these oral bacteria activate ACPA B cells, which result in affinity maturation and epitope spreading to citrullinated human antigens, according to the findings.

Orange and Robinson discussed the background of their study, their surprise at the findings, and what the results may mean for practicing rheumatologists.

Why was the association between periodontal disease and RA studied?

Orange: Our group studied flare-ups of RA. Like many common, chronic inflammatory diseases, RA has a fluctuating course in which patients can do well one day but then have a flare-up of disease activity the next. By having a small group of patients send us blood samples on a frequent, regular basis, we were hoping to gain insights into why that happens.

Healio: How often and how regularly do you visit?

The samples consisted of three drops of blood collected from the patients at home and mailed to us once a week for years. If they flared, we were able to track what was changing in their blood prior to the flare.

Healio: Why did you focus on RA flare-ups?

Our previous paper demonstrated that we were able to identify these really interesting immune activation signatures around flare-up times. In particular, those results revealed that 2 weeks before flare-ups, there was a B-cell signature as well as a PRIME cell signature, a fibroblast-like cell.

These patients were feeling well, they were not experiencing symptoms, but they were about to flare up. We had a lot of questions about what would trigger these PRIME cells and B cells. In our previous paper, we hypothesized that a microbial trigger may trigger this type of response.

That’s why you wrote this paper based on your findings.

The purpose of this paper was to determine if a microbe was responsible for flares. To do that, we removed all reads that aligned to the human genome and analyzed what was left behind. We then compared those reads with the data from the human microbiome. In order to deconvolute our blood gene expression data, we used that information.

As a result of our study, we found that patients with periodontal disease were experiencing repeated, frequent episodes of an array of oral commensal bacteria entering the bloodstream, not just the dominant bacteria, but basically all bacteria normally found in the mouth. While the patients with recurrent oral bacteremia underwent dental procedures for their periodontal disease during our study, these episodes were independent of those procedures.

Patients with periodontal disease have leaky gums that allow oral bacteria into their blood more frequently than we originally believed. Patients do not have any symptoms when this occurs, so they do not know it’s happening.

Was the goal to connect that to RA at this point?

It’s exactly what Orange said. To figure out why this had anything to do with RA, we compared the oral bacteria inferred load in the blood with the human gene expression response, and we found that this robust gene expression was correlated with an inflammatory monocyte that appears in rheumatoid arthritis-inflamed joints.

When you started collecting the blood samples, did you expect to find this? Or did you expect something else?

We were not expecting this. If anything, we were expecting a viral trigger. If there was a microbial trigger, we thought it would be a single microbe, but that wasn’t the case. A patient’s blood never contained just one species of oral bacteria – nearly all the oral bacteria in their mouths were present, and the abundance reflected the abundance in the mouth.

When we saw that these samples had oral bacteria, and that they were coming from patients who we knew were having repeated dental procedures, we decided to investigate. Additionally, we understand that rheumatoid arthritis patients are more likely to suffer from periodontal disease.

As a matter of fact, Dr. Orange studied human gene responses to flare and mapped them out really elegantly. Although she saw the B-cell and PRIME-cell signatures, she was surprised to find multiple bacterial genes that mapped to commensal oral bacteria in the non-human genes. We had no idea that oral bacterial genes could be detected in RA blood.

Healio: How did you proceed after you made this discovery?

Orange: We validated what we observed with the human gene expression response by taking oral commensal bacteria and putting them in normal blood. When oral bacteria get into anybody’s blood, they will produce an inflammatory monocyte gene expression response. This prompted us to wonder whether periodontal disease is associated with rheumatoid arthritis.

To explain this association, we concluded that patients with rheumatoid arthritis must have additional, more specific immune responses to oral bacteria. As a result, we partnered with Dr. Robinson’s lab. He studies the B-cell response in patients with RA, which is extremely specific.

Robinson: We had been sequencing B-cell responses in RA for many years, and finding in addition to IgG B cells, there were also prominent IgA B cells that were already heavily mutated. Additionally, the same IgA B-cell clones were persisting for many months or years. We thought that there could be some kind of mucosal triggers. So, one of the first things we did when Dr. Orange identified certain oral bacteria in RA was to ask whether the antibodies encoded by these persistent IgA B cells bound these same bacteria.

One element that convinced us that what we were studying might be real was that they did. Secondly, these bacterial RNAs were associated with human RNA inflammatory macrophage gene expression when they were found in the blood. In addition to being related to B cells, they were also related to innate immune cells.

Healio: Does this indicate causality one way or the other? Could oral bacteria in the blood cause RA, or is it the other way around?

Orange: We studied patients with established rheumatoid arthritis, so we cannot tell anything about causes of events in RA. It is difficult to establish causality with observational data. Three studies, however, indicate that patients with RA and periodontal disease are more resistant to treatment.

Our findings provide a plausible mechanism to show that if you have periodontal disease and leaky gums, bacteria are constantly getting into the blood and triggering an immune response of RA. Understanding why it would be difficult to treat this subset of patients with rheumatoid arthritis can help you understand why it is so difficult.

Healio: What are the implications of this finding for an average practicing rheumatologist?

Orange: It would be a good idea to conduct some studies to determine whether treatment for periodontal disease would make treating refractory RA easier.

Healio: What would a study like that look like?

Orange: We are still working on those details.

Robinson: Periodontal disease is complex. It is not just the bacteria that cause periodontitis, but also the mucosal fragility it induces that causes RA activity.

A number of dental products are available to treat periodontitis, but there are also more aggressive treatments like gum grafting and shaving, which seem like pretty radical approaches for RA. There are mouthwashes and better ways to brush and floss, but there are also more aggressive treatments like grafting gums and shaving teeth. However, it is unclear which types of interventions will work best in a broader population and then how we will find the benefit our patients need.

Orange: It is also important to note that rheumatoid arthritis is not curable, and it can be debilitating and costly to treat. In contrast, periodontal disease is quite treatable. It is now up to us to prove that changing periodontal disease activity can have a positive effect on patients with RA.